Paul O'Sullivan

UK Sales Director, Threatscape

Let’s talk email compromise and business email security.

It’s not a new issue. In fact, to move forward we must look back to understand how it came to be the challenge it is today. Why, despite email communication emerging in the mid-late ’90s, are we still struggling to effectively secure it?

Whether because email wasn’t conceived with security in mind, or owing to people’s susceptibility to that which looks like legitimate communication, it’s essential that business email be secured.

Unfortunately, businesses are continually compromised through email (Business Email Compromise, or BEC) – via ransomware, invoice fraud, loss of IP – and it’s arguably the easiest attack vector for criminals to leverage.

With this in mind, let’s reflect on the key stages of the evolution of email cyber security, and the new technology producing genuine security results.

The dawn of the Internet and email (the ‘90s)

Back in the mists of time – the mid-‘90s – Internet adoption gained traction, and this resulted in email becoming an increasingly popular method of communication among larger organisations.

As we approached the end of the ‘90s, forward-looking organisations realised that their email systems could be vulnerable to attack. This brought about the introduction of security software that “plugged into” email servers, with leading Anti-Virus (AV) vendors like F-Secure, McAfee, and Symantec all offering a solution that was installed onto email servers (Microsoft Exchange, for example) in a similar way to desktops and servers.

While this approach seemed sensible at the time, events toward the end of the ‘90s proved the model to be less effective as the popularity of the Internet and email exploded.

Although consumers were typically using dial-up connections, businesses were signing up for “always-on” broadband which meant that the spread of email-borne viruses was almost instant. Two notable examples that helped to evolve the email security marketplace were Melissa and then the LoveBug (aka ILOVEYOU) virus.

What made these attacks particularly effective was the use of Microsoft macros to help with their distribution – enabling them to access the address books of recipients and then email the virus to all contacts. The Melissa virus saw the first attack in March 1999, followed by the LoveBug in May 2000, which once again leveraged the address book to propagate – this time using a VB script.

The challenge with both attacks was that IT admins were overrun, unable to stop the spread of the viruses, and there was mass disruption for victims in both cases.

Fortunately, someone had thought of an idea to address this new challenge.

The noughties – SaaSy and SEGsy

Back in the mid-’90s, a fledgling Internet Service Provider (ISP) from Cirencester, England, was established to target businesses rather than consumers. As part of their business model, they focused on adding new services to their connectivity offering to better differentiate their business – this included offering an internet security appliance, and fax to email.

In one of their regular brainstorming sessions, the team had pondered the question, “Why don’t ISPs scan email for viruses?”

This session led to the company implementing a new email filtering solution using a regular AV engine. Bets were placed on how long it might take for the new filter to trap a virus, and they were stunned when it occurred in only five minutes. The new filter was offered as a free add-on to friendly customers, but eventually it was discovered that viruses were still getting through the engine, so they added another AV solution.

At the same time, one of the ISP’s engineers had been watching the exploit chatter in an online forum and used these insights to help write a Perl script to look for common characteristics of these viruses. Eventually this script was bolted alongside three AV engines and then the email filtering service went live.

Quickly realising the value of this service, other ISPs began asking to buy the new technology, and so they started a stand-alone company (StarLabs) to resell it to other ISPs. That didn’t last long thanks to a legal challenge from a similarly named company specialising in biological virus research, so they had to consider another name.

One trip to the Crown in Cirencester later and the Head of Marketing had come up with their new name: MessageLabs. Their success in stopping the Love Bug virus prompted them to take out a full-page advert in the Financial Times, which catapulted the small ISP and fledgling email filtering company to the global stage and from 2001 saw the start of its meteoric growth.

The spam boom

Meanwhile, not too far away in Theale (UK), a company called Net-Tel had rebranded to Clearswift and raised venture capital funding on the back of its own success in email filtering. The subsequent acquisition of Content Technologies from Baltimore Technologies (itself briefly a dot-com darling) gave the MIMEsweeper product a means to scan email messages and led to the development of their email gateway appliance. The market was very much split between either “on-premise” or “in the cloud” solutions, with other names such as Barracuda, Ironport, and MailMarshal amongst popular on-premise solutions – and Postini, BlackSpider, and FrontBridge among the players for cloud scanning.

Email viruses started this market segment, what accelerated it was the explosion of spam. Spam very quickly overtook viruses in terms of the percentage of overall emails – presumably as it was easier to bypass defences (unlike viruses) and there was a potential monetary reward.

Not only did this drive the take-up of email security solutions, but also contributed to major consolidation of vendors. FrontBridge sold to Microsoft in 2005; Blackspider sold to SurfControl for £19.5m in 2006; Ironport sold to Cisco for $830m in 2007; Postini sold to Google later that year for $625m; and MessageLabs sold to Symantec in 2008 for $695m. In short, the mid-late noughties was a busy time for acquisitions, illustrating the importance at the time of solving the problem (or having the technology in your portfolio to sell to your customers).

Despite this consolidation, there were still new entrants in the market – including Proofpoint in the USA and Mimecast in the UK (not to be confused with MIMEsweeper). They both entered the market and grew on the back of acquisition activity – the former focusing on spam filtering efficacy, and the latter offering email archiving and email continuity services (which provided a lifeline for administrators wrestling with clunky exchange servers!). Spam volumes made up approximately 90% of email traffic towards the latter part of the decade but were beginning to tail off as a new threat began to emerge.

The '10s – phish for everyone

As the leading vendors continued to provide high levels of protection against spam, a new technique began to emerge: phishing. Instead of a distributed architecture to send broadly the same emails, criminals were shifting to a method that tricked the recipient into clicking a link – which would typically lead to a new, malicious website, or to one that looked familiar (e.g., online banking, corporate intranet, etc.) in order to gain the recipient’s login credentials.

While “normal” spam and malicious attachments were still prevalent, this new technique gained momentum and was attributed to almost all of the major breaches during the ’10s. The most targeted of all phishing attacks was spear phishing, usually a single email sent to a single individual – often a senior figure in a business, for which their compromise would deliver a huge prize for the attackers. By using a technique called social engineering, the attackers could create email content specifically designed to trick the recipient into clicking on a link or sharing information.

The rise in this type of attack was even more difficult to detect and prompted the established vendors to build (or acquire) new technology. Proofpoint acquired Armorize, whilst Cisco, Ironport and Mimecast all developed their technology in-house – meanwhile a new entrant called FireEye entered the marketplace. The approach taken was to check the email content in a “sandbox” environment, with a virtual machine visiting the website links and observing what happened next.

The attackers became aware of this, and so wrote their code to try and differentiate between human behaviour and the predictable pattern of a sandbox – constantly upping the stakes and the complexity. The challenge with sandboxing meant that whether on-premise or in the cloud, it required significant resources, so the on-premise approach gave way to cloud-based email filtering, although this often saw delays to email delivery. Conversely, the attackers also used cloud computing to better orchestrate their attacks – enabling them to access greater scale, whilst still making each email highly personalised to the recipient.

As the end of ’10s approached, the predominant threat had shifted from common spam and viruses to phishing email, and a new trend in the form of “ransomware”. This latest threat saw attackers compromising the recipient’s machine (or the wider systems) and demanding a ransom in Crypto currency, predominantly, Bitcoin. Very quickly, phishing and ransomware became the top issues for security teams to try and address, spawning a rise in security awareness solutions to better educate end users.

The cloud and the rise of machine learning?

Throughout the ’00s and the ’10s, the use of cloud computing for email security provided a filtering “step” in between the Internet and the destination email servers. In the noughties, it meant that the junk was filtered before it reached the corporate mail servers, which had huge appeal. The same was true to an extent in the ’10s, because of the computing limitations of sandboxing appliances “on-premise”.

Given the trend towards email servers “in the cloud” – alongside a general trend towards cloud computing for corporate infrastructure – it opened up the potential to address the challenge of email filtering in a slightly different way.

Back in 2019, there were suggestions of using API connections into email systems (Office 365 and Gmail) to look for anomalies, thus doing away with Mail Exchange record changes and having another provider in your email flow. Over the course of the last two years, vendors have emerged that take this approach and either adopt the traditional “scan for malicious code” or “scan for anomalies” in the header/content approach.

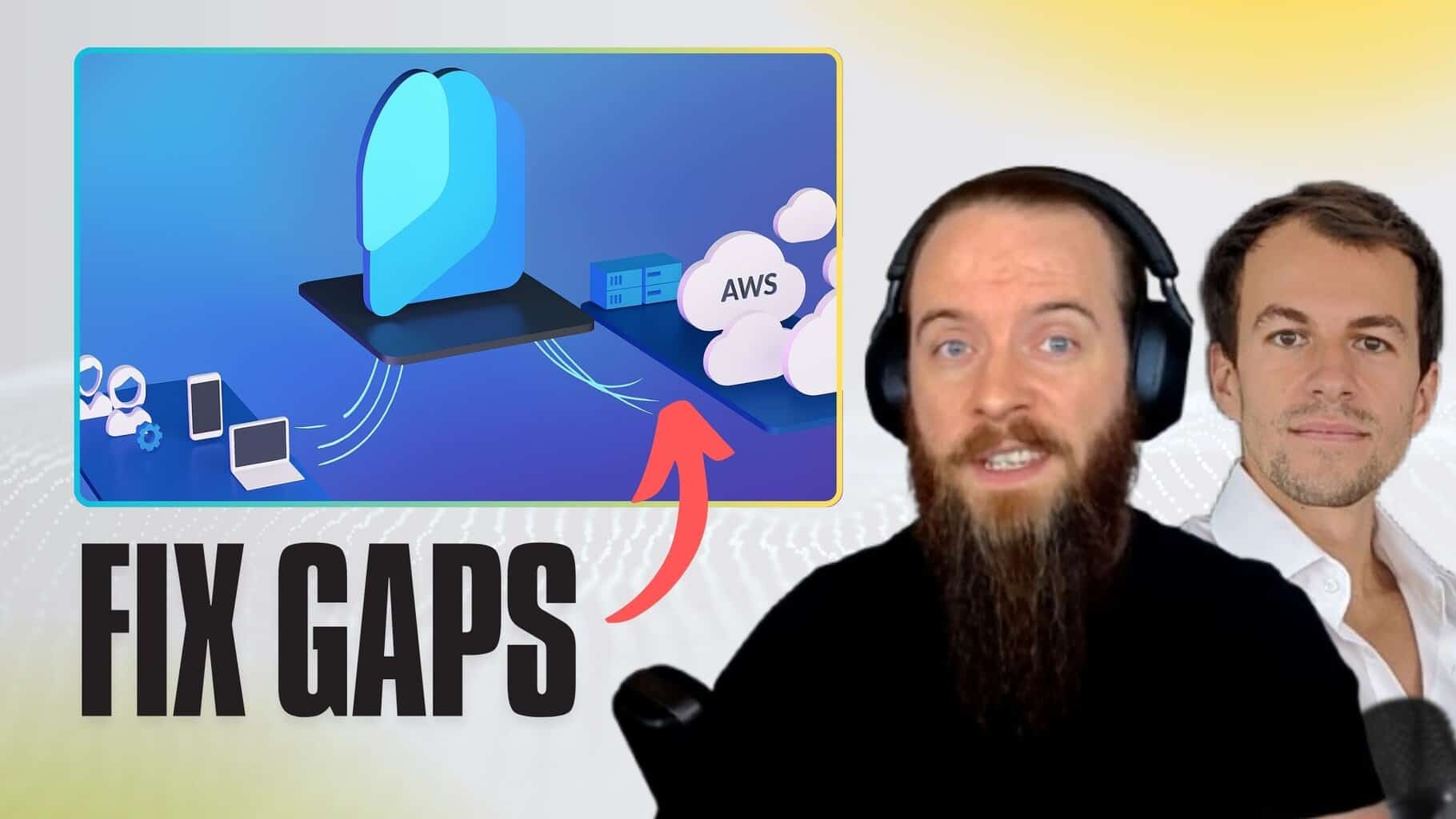

Behavioural AI for email cyber security

An immediate benefit of this method is that instead of hoping that the Server Email Gateway (SEG) method of filtering email (i.e., during ingress or egress) will catch something, the entire email system can be checked for anomalies.

This means that in the event of a slow, subtle attack over time (which might have been missed by traditional defences), these anomalies have a better chance of being detected in the context of the entire message store and what a “normal” email should look like, maintaining a consistent defence.

While not doing away with “traditional” email filtering, this offers the potential to shift away from third party SEG solutions, and instead utilise the filtering from Microsoft, Google, and other mail providers alongside behavioural analytics to look for the less obvious attacks. A disruptive shift in email security is dawning…

Find out more with Abnormal Security

Find out more about how Abnormal Security uses behavioural AI to profile known good behaviour and analyses over 45,000 signals to detect anomalies that deviate from these baselines, delivering maximum protection for global enterprises.

After running a Proof of Concept, one of our customers discovered almost 400 instances of email compromise, which had completely bypassed their existing SEG solution.

Click here for a complimentary email security risk audit.